Deconstructing My Father – Part One

Deconstructing My Father is a linear narrative about a weird point in my life – late 2018 / early 2019 (I’m not entirely sure) – where my estranged father developed dementia and I had to take over running his life and the lives of both of my little brothers. I started documenting it in a weird journal using pseudonyms for my brothers and family. It was probably the most stressful time of my life.

It Begins

“Where are we going?” My father asks feebly from the passenger seat.

“To the doctor.”

“Why? I just went to the doctor.”

“When,” I ask, trying to sound more clinical than concerned.

“Monday, when Travis flew out.”

I’m Travis. I haven’t flown anywhere in months. Sitting next to me in the car my father has forgotten who I am.

“I’m Travis.” I tell him.

He stalls for second. His mind racing trying to cover his tracks so it doesn’t seem like he’s helpless. This will become a pattern.

“I meant Ryan. Monday when Ryan flew out. You dropped him at the air base. He had an operational mission in Thailand.”

The air base he’s talking about has been closed since the 90’s. My oldest little brother, Ryan, is 23 – sixteen years my junior – not in the military and lives 5 hours away in San Luis Obispo. I don’t tell him this. I don’t know, really, what’s going on in there.

This started two days ago when my youngest brother, Patrick – 21 and almost 19 years my junior – texted me that our father was asking about his truck (one that Patrick totaled three years ago) and wondering where the dogs were (dogs he hasn’t had for a decade). And now here we are heading to the doctor’s office in order to determine what the hell I’m supposed to do with a father whose grasp on reality is tenuous. At best.

I need to tell you, reader, up front; my father and I do not have a great relationship and we never have.

At first it was non-existent (he left my mother and I when I was only six weeks old. I was the one that demanded bi-weekly visitation at ten years old.)

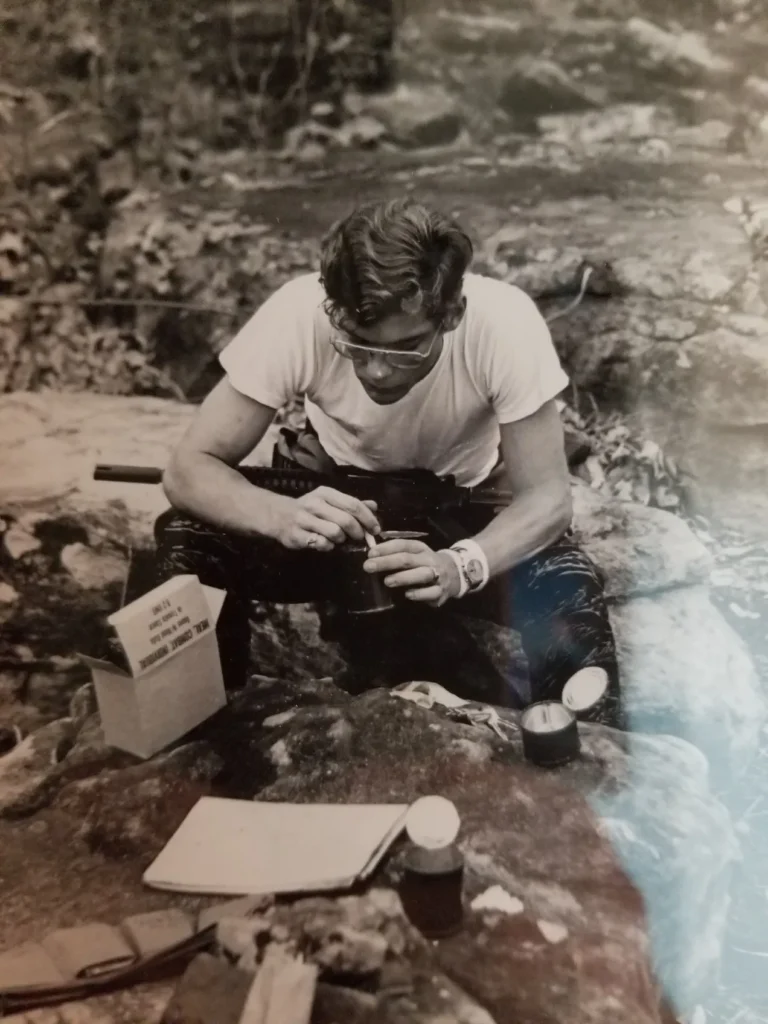

Then it was adversarial. My father, a strict, hardline military man, had little patience for his artsy fartsy son. At eleven years old I protested the first Gulf War because the only thing I knew about war was what I saw on TV – and in war people died. I didn’t want my dad to die. So I protested and I told him about it, gleefully and naively, in a letter that I wrote to him.

My father, a scarred Vietnam Veteran, responded in a letter that arrived on my twelfth birthday, where he called me names that I didn’t know the meaning of. I cried myself to sleep that night while my mother screamed on the phone with my father’s fourth wife.

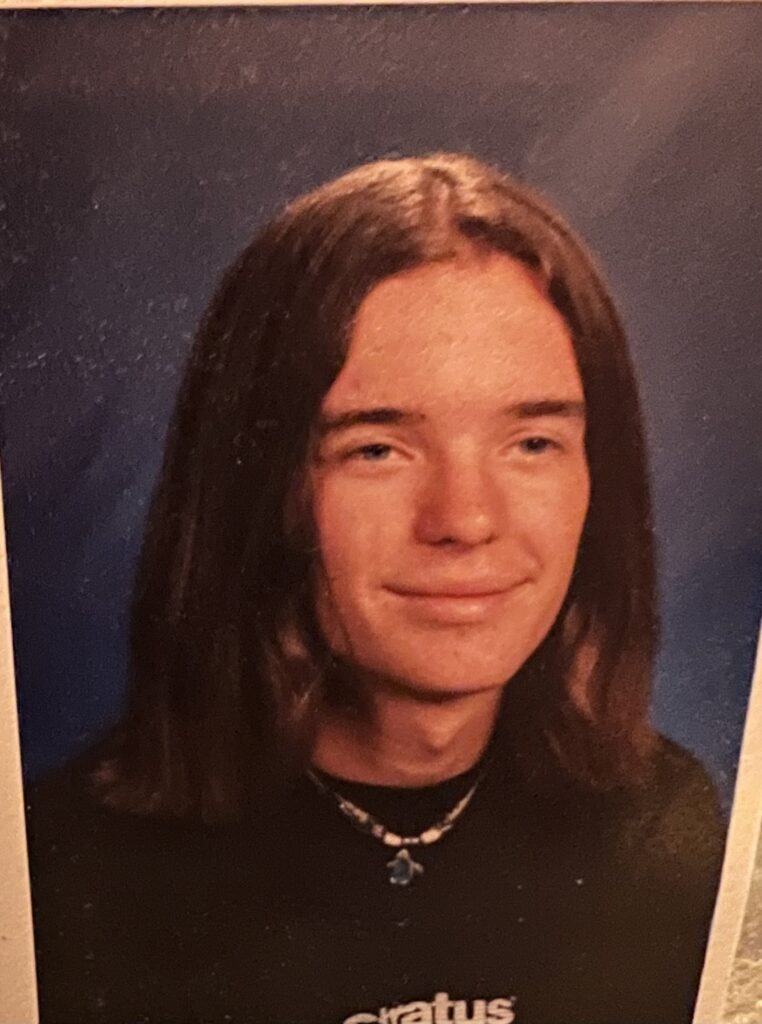

As a teen he had no tolerance for my grunge music, my desire to paint my nails black and my plans to wear a dress to prom. He never called me faggot to my face; but he came close.

In my late twenties and early thirties the relationship was inverted. My father, a recent widower, had no idea how to parent and now found himself in charge of my two young brothers. He called me, recently married and raising an infant, for parenting advice. But he resented having to. He resented it even more when I was right.

I don’t want to lie to people. This isn’t a hallmark story.

And now, here we sit, a begrudging son taking on the burden his brothers are too young to shoulder and a confused father who is incapable of saying thank you, who never said I love you, who doesn’t know who the fuck I am.

This is the chronicle of what it takes to deal with an estranged parent who has lapsed into dementia. This is the chronicle of what it takes to forensically dissect the life of your parent who can’t tell you how his bills get paid, how much his youngest sons’ college tuition is or even where he left his car keys. This is a chronicle,a journal, of an almost forty year old son that has to figure out his father’s world based only on clues that you can find in the piles of mail left around the house and the steps it takes to organize the remnants of his legacy so that nothing falls apart.

This is how I ended up parenting my parent one last god damn time.

Maybe it will help you to know that you’re not alone in having shitty parents. Maybe I can help you understand what it takes to dissect a human life from the electronic trail they leave behind. Maybe, like Leonard from Memento, I can help you learn, through my own follies, the systems you have to put in place to organize the endless amount of data it takes to run not just someone else’ life; but also the lives of their kids.

Maybe this is just therapy.